The Northern Pietà of Finland: Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Lemminkäinen’s Mother

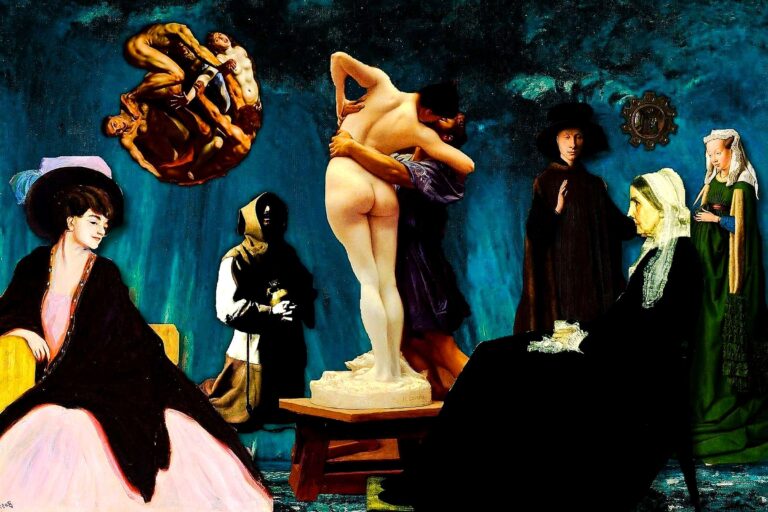

Gothic Modern, after captivating audiences at the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki, is now dazzling visitors at the Albertina in Vienna until the end of the year. The show sticks with you. Both for the clever idea behind it and for the works that keep coming at you like one surprise after another. The way Northern artists of the modern era reinterpreted Gothic art gave birth to what critics now call Gothic modern. In our own ranking of the most remarkable exhibitions of 2025, this show easily makes the top ten.

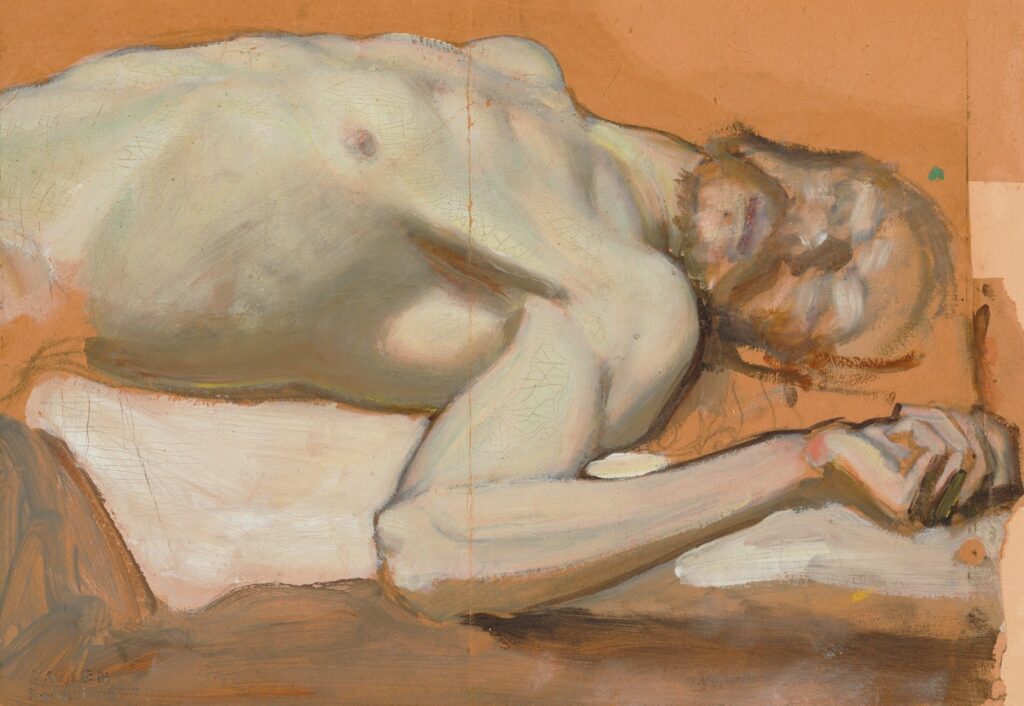

Among its many treasures, one canvas stands out as impossible to overlook. It strikes directly at the heart. Lemminkäinen’s Mother by Akseli Gallen-Kallela. This work is far more than an illustration of the Finnish national epic Kalevala. It is at once a myth, a family drama, and an expression of personal grief, woven together on a single canvas.

Kalevala and Finnish Identity

The Kalevala is Finland’s national epic. In the 19th century Elias Lönnrot, a physician, philologist, and folklorist, rode the countryside across Finland and Karelia with a notebook to collect oral poetry. Much of this material came from Karelia, the borderland region where ancient song traditions had survived most strongly, even as they were fading elsewhere in Finland. By gathering these poems, Lönnrot created a literary monument that became the beating heart of Finnish identity at a time when the country was still a Grand Duchy under Russian rule and long influenced by Sweden.

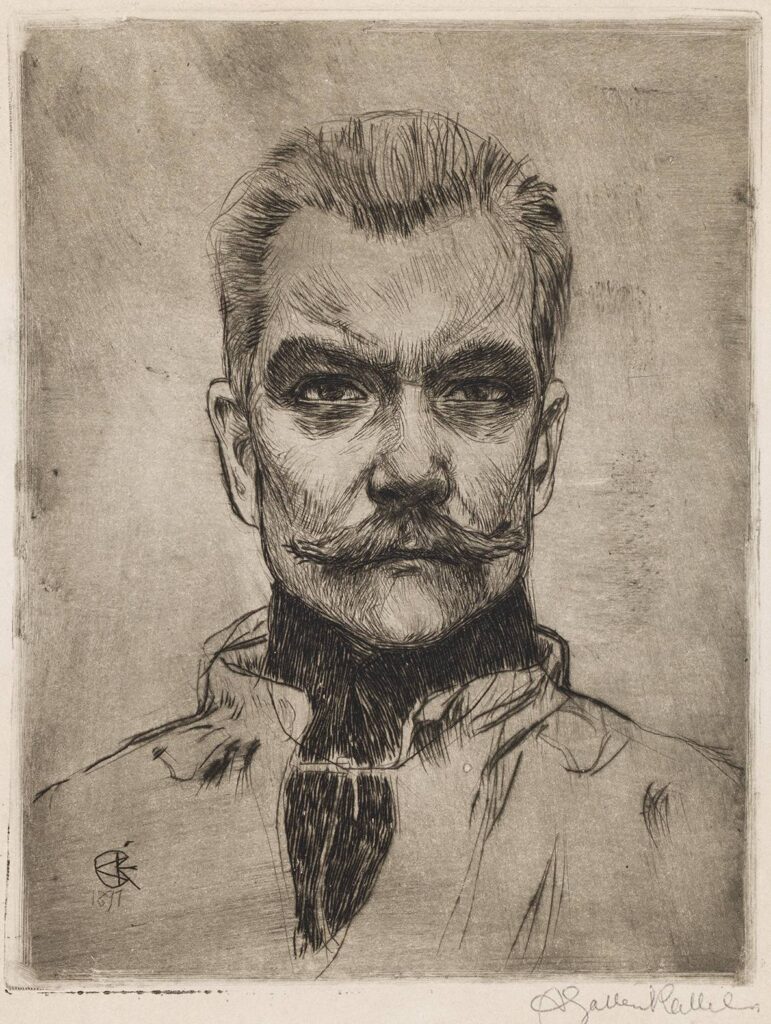

For Akseli Gallen-Kallela this was not just folklore but destiny. Born in 1865 in Pori, in a Swedish-speaking family of the Russian Empire’s Grand Duchy of Finland, he later chose to “finnicize” his name and identity, becoming one of the central figures of the national awakening. His life moved in step with Finland’s own struggle. A country fighting to be seen as itself, not as a province of others.

After traveling to Karelia and immersing himself in its songs and landscapes, Gallen-Kallela began to paint the Kalevala with unprecedented intensity. Works such as The Defense of the Sampo , Lemminkäinen’s Mother, and Joukahainen’s Revenge gave visual form to mythic drama. Through these canvases, Gallen-Kallela helped turn the Kalevala into a cornerstone of modern Finnish identity.

And among all these paintings, none is more personal and haunting than Lemminkäinen’s Mother, often called the Northern Pietà.

Who was Lemminkäinen?

In the Kalevala, Lemminkäinen is the unruly hero: part warrior, part sorcerer, and part heart-throb. He is often described as a striking red-haired figure whose charm is matched only by his arrogance. More folk trickster than noble knight, he is a troublemaker who wins women, stirs fights, and ignores warnings.

His greatest challenge comes when he travels north to Pohjola, the land of shadows, and attempts the impossible task of killing the sacred swan on the River Tuonela. A blind herdsman strikes him down, his body is cut apart and thrown into the dark waters. In some versions of the epic this is the end, but in others his mother restores him to life. It is this version that Gallen-Kallela chose to immortalize. The real power of the story begins after the death of Lemminkäinen. Here myth meets personal grief, and the painting becomes less a legend than a reflection on loss and the hope of return.

The artist did not seek a model for the figure of the slain hero. He turned to himself. In his studio he staged the scene, lying in the pose of the lifeless Lemminkäinen, and most likely with the help of mirrors, he produced sketches that later fed into the final composition. The result is more than myth on canvas. The artist’s own body became the template for the epic’s fallen son.

Death

The hero Lemminkäinen meets his end when he ventures into the realm of the dead to slay the sacred swan on the River Tuonela. Tuonela is the Finnish counterpart to the underworld, and the swan is its guardian, marking the boundary between the living and the dead.

For Gallen-Kallela this episode was never just a legend. In 1895 he lost his first child, a three-year-old girl, Impi Marjatta, who died of diphtheria. From that moment the theme of death became a permanent presence in his art.

Only a few years later, in 1898, tragedy struck industrialist Fritz Arthur Jusélius, whose eleven-year-old daughter Sigrid died of tuberculosis. In her memory he built a Mausoleum at Käppärä Cemetery in Pori and invited Gallen-Kallela to paint its interior. The result was a cycle of frescoes, the most famous being By the River of Tuonela.

Here is the motif of the swan and the black river directly echoes Lemminkäinen’s Mother. In one painting the swan remains white. In the other it turns blood-red. Without this bird, you’d hardly know it was a river at all. That’s how deep the darkness runs. The swan becomes the lone marker of the frontier between worlds. In this way, the artist fused the myths of the Kalevala with the universal grief of parents who lose a child.

The Jusélius Mausoleum frescoes became legendary in Gallen-Kallela’s oeuvre. The originals were destroyed by fire in 1931, but a few years later, his son Jorma restored them faithfully from his father’s sketches. Today the Jusélius Mausoleum remains the most famous site in Pori, celebrated both for its architecture and for the resurrected frescoes of Gallen-Kallela.

Mother

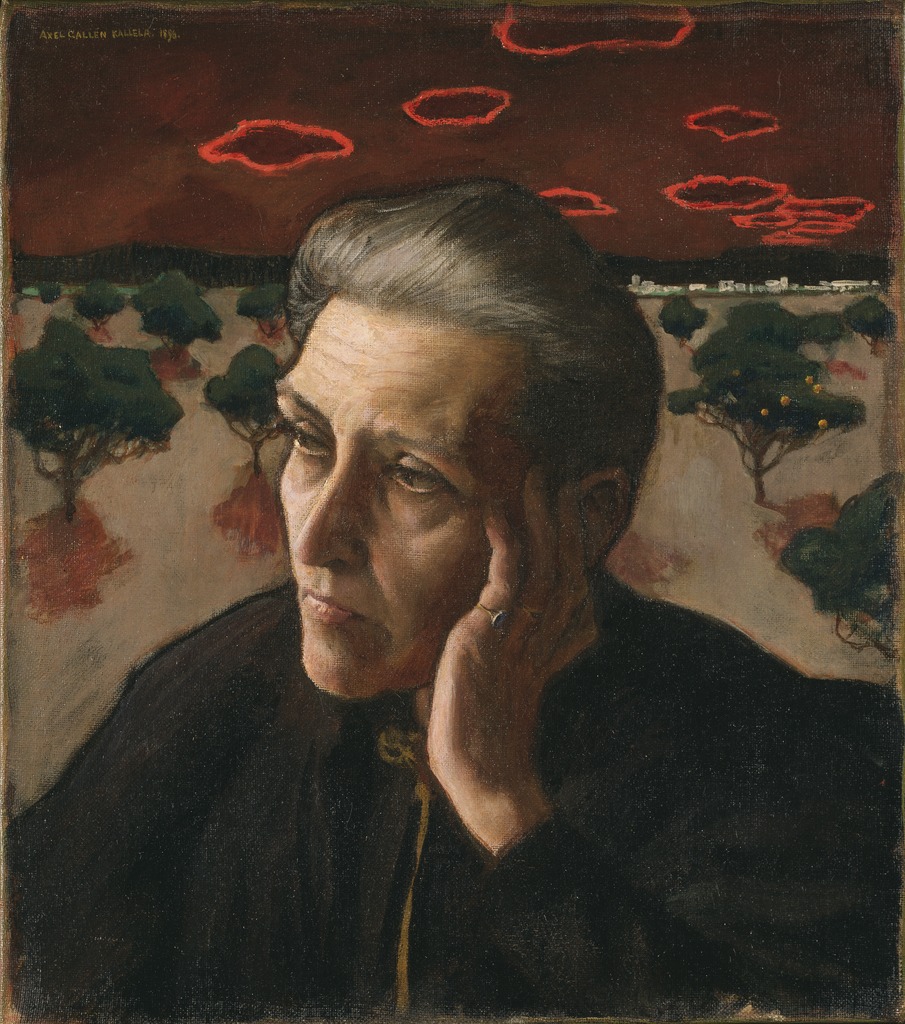

Here we are not looking at an abstract “maternal figure” but at a very real woman. Anna Matilda Gallen. She was the artist’s mother. In 1896, Akseli painted her in a small and hypnotic portrait. Executed in the spirit of Renaissance portraiture, the work shows a woman whose face seems modeled out of light. Her gaze is direct and restrained, but the background unsettles us with its strange forest and ominous red clouds.

It was at this moment, while “testing” his mother as an archetype, that Gallen-Kallela found her most powerful role. Her face became the prototype for the monumental Lemminkäinen’s Mother. His mother posed as the model, and the personal and mythical became inseparable. Just as in the epic, where Lemminkäinen’s mother gathers her son’s dismembered body from the dark waters of Tuonela and binds it together with charms and ointments, so too does Anna Matilda appear here as both a mother and a myth. In the painting we see the body of the hero whole, but still lifeless. Her upward gaze recalls the iconography of the Pietà, where Mary mourns Christ, but here the story pauses on the threshold of resurrection. She awaits the bee who will bring enchanted honey from the god Ukko, the final ingredient to restore her son’s life.

In Gallen-Kallela’s own life, this symbolism was not incidental. In his youth, it was his mother who encouraged his passion for painting, while his father hoped for a more “practical” career. Throughout his life she remained a close friend and steady support. The two canvases, the intimate portrait and the monumental epic scene, form a diptych of sorts. One whispers unease in its background, the other confronts the black river of death with the power of maternal love.

In Lemminkäinen’s Mother, personal grief, ancient myth, and the stark symbolism of death converge into an image that is impossible to look away from. While the exhibition features several of Gallen-Kallela’s Kalevala-inspired works, it is this “Northern Pietà” that radiates the most profound energy. All these paintings were executed in tempera rather than oil, giving them a distinctive matte glow and intensity that heightens their emotional force.

Can’t make it to Vienna for the exhibition? Let the catalog bring it to you instead. It is the kind of book that deserves a place on your shelf, and we are pretty sure you will read it cover to cover.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

03 Oct 2025

Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages…