Art Exhibitions We Loved This December

Most of this season’s blockbuster exhibitions began their march back in October, accompanied by headlines, queues, and endless social media coverage. Instead of repeating what everyone is already talking about, from the Davids to Fra Angelico and the usual suspects, we decided to look in a slightly different direction.

What follows is a selection of quieter, more intimate exhibitions. They may not dominate the news cycle, but for attentive viewers they offer something just as valuable. The near-ritual silence of Segantini’s landscapes, the solitude and restraint of Helene Schjerfbeck’s portraits, the strange and persistent mythology of the unicorn. These are exhibitions that reward patience, slow looking, and genuine curiosity.

Giovanni Segantini

Museo Civico di Bassano del Grappa, Bassano del Grappa, Italy

October 25, 2025 – February 22, 2026

When visiting the museum’s website, a notice appears immediately: due to high visitor numbers, there may be a wait to enter the exhibition. The wording is polite and understated, but the message is clear. The Segantini retrospective is drawing real attention.

Giovanni Segantini was one of the central figures of Italian Divisionism and one of the most distinctive artists working in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century. His name may be unfamiliar to many American readers, but his work occupies a unique position between landscape painting and Symbolism, using light and the Alpine world to reflect on faith, labor, and inner life.

The exhibition is conceived as a full retrospective. Around one hundred masterpieces from public and private collections in Italy and across Europe are brought together, tracing Segantini’s development from early realist works to the mature paintings in which light and symbolic meaning take center stage. This is not a selective display or a survey of picturesque landscapes, but a carefully structured overview of his artistic evolution.

The curators place particular emphasis on recent research related to one of Segantini’s best-known works, Ave Maria a trasbordo. Close analysis of materials and painting technique has led to new readings of this familiar image and brought previously overlooked details into focus.

During the 1880s, Segantini produced several versions of Ave Maria. A family with sheep crosses the lake by boat and encounters the call to prayer while still on the water. There is no church, no gesture, no drama. Only water, light, and a brief pause in the journey. It is this moment of quiet suspension that makes the painting so memorable.

Still, despite the attention given to Ave Maria, our personal favorite remains Early Mass. It is a painting one can return to repeatedly, especially for the steps, constructed with such precision and inner rhythm that they seem endlessly absorbing.

Following its presentation in Italy, the exhibition will continue in Paris at the Musée Marmottan Monet, on view from April 29 through August 16, 2026

Wax Upon a Time. The Medici and the Arts of Ceroplastics

Uffizi Galleries, Florence, Italy

December 18, 2025 – April 12, 2026

Renaissance art is usually associated with marble, bronze, and oil painting, materials meant to endure. Wax, by contrast, is fragile and unstable. It melts, cracks, and ages. This is precisely why the history of wax sculpture at the Medici court feels so unexpected today.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Medici created one of the most popular and widely discussed collections of wax figures in Europe. These objects existed at the intersection of art, science, and religion. They were used for devotion and commemoration, for the study of the human body, and for courtly display and intellectual experimentation.

The fate of this collection was complex. In 1783, roughly forty years after the death of the last Medici heir, Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine ordered the sale of nearly the entire wax collection at auction. The objects were dispersed into different collections, and only now has a portion of this remarkable material been reunited in the galleries of the Uffizi.

The exhibition brings together around ninety works. Wax figures are shown in a carefully constructed thematic dialogue with paintings, sculpture, cameos, and objects made in pietra dura, the luxurious Florentine technique of hardstone inlay so closely associated with Medici taste. This approach allows visitors to see wax not as a curiosity, but as an integral part of Renaissance visual culture. Among the more unexpected encounters is the posthumous plaster mask of Lorenzo the Magnificent, notable for its strikingly calm and almost content expression.

Several wax compositions leave a particularly strong impression, including Screaming Soul in Hell and The Corruption of Bodies. These works are memorable not for theatrical effect, but for the way they engage the viewer’s imagination and reveal how closely Renaissance artists connected the body, belief, and transformation.

Wax Upon a Time is an unusual exhibition in both structure and concept. Rather than offering a conventional survey, it reconstructs a cultural world in which wax played a central role, revealing a practice that was once both sophisticated and influential, yet later forgotten.

If, after visiting the Uffizi, you feel inclined to continue this conversation about wax with greater scientific precision and an almost unsettling realism, we recommend a visit to Florence’s La Specola museum, home to its extraordinary Medici-era anatomical wax collection.

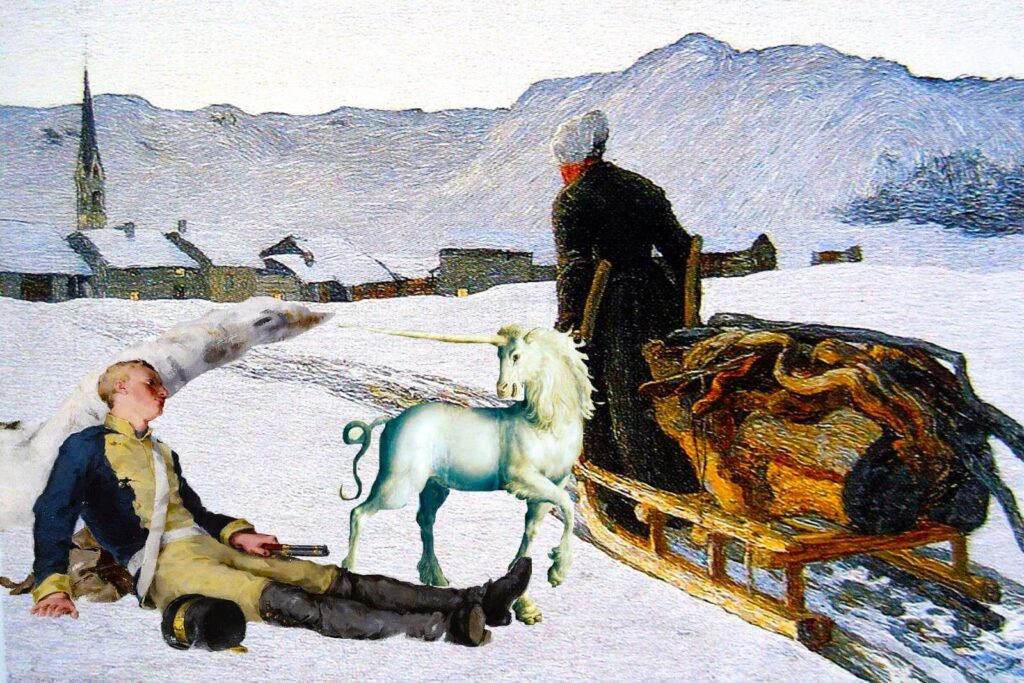

Unicorn: The Mythical Beast in Art

Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany

October 25, 2025 – February 1, 2026

Perhaps one of humanity’s more underappreciated losses was giving up belief in the unicorn. After all, everyone needs, from time to time, the hope of encountering such a fairy-tale, decorative creature. And if a living miracle is no longer on the table, the exhibition at the Museum Barberini offers a comforting alternative — a chance to see how the unicorn has survived for centuries in the imagination of artists.

Unicorn: The Mythical Beast in Art traces the image of the unicorn from antiquity to the present, showing how its meanings and functions have shifted over time. Across different periods, it appears as a religious allegory, an object of curiosity, or a projection of utopian imagination.

What makes this exhibition particularly compelling is its scale. The museum has undertaken an ambitious effort, bringing together around 150 works from approximately 80 museums, galleries, and private collections. This breadth allows the visual history of the unicorn to be seen as a continuous and evolving narrative rather than a series of isolated examples.

The exhibition includes paintings, works on paper, illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, sculpture, and video art.

One of the most engaging aspects of the exhibition is the way the unicorn moves between the sacred and the secular. In medieval art, it is closely tied to Christian symbolism and ideas of purity. In later periods, it becomes an emblem of rarity, desire, or knowledge. Contemporary artists approach the figure with irony or critical distance, while still relying on its immediate recognizability.

The result is an exhibition that works on several levels at once. It offers a serious investigation of iconography, while also providing a visually rich and surprisingly cohesive experience. Above all, it shows how a mythological creature continues to adapt, persist, and acquire new meanings within the history of art.

The exhibition catalog is expected by the end of January 2026

Impressionism in Germany. Max Liebermann and His Times

Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

October 3, 2025 – February 8, 2026

When Impressionism is mentioned, France and Paris tend to dominate the conversation. Germany is often treated as a secondary chapter, if it appears at all. This exhibition in Baden-Baden quietly challenges that familiar narrative.

Rather than presenting Impressionism as a style imported wholesale from France, the show looks at how it was adapted and reshaped within a German artistic and social context. At its center is Max Liebermann, a pivotal figure in German art at the turn of the twentieth century and a key mediator between French painting and German visual tradition.

Liebermann was among the first German artists to consistently embrace Impressionist principles such as an emphasis on light and color, loose brushwork, and scenes drawn from everyday life. At the same time, his work never reads as imitation. German Impressionism emerges here as more restrained and structured, with a stronger sense of form and composition than its French counterpart.

The exhibition brings together more than one hundred works, including paintings, drawings, and prints. It places Liebermann in dialogue with contemporaries such as Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and Fritz von Uhde. Together, these artists reveal the breadth of German Impressionism, from garden scenes and figure studies to landscapes and views of urban life.

This exhibition is particularly rewarding for viewers who assume that Impressionism is a closed and well-defined chapter in art history. It gently shifts perspective, reminding us that the story of modern painting developed across multiple centers, often in parallel rather than in a single, dominant line.

Starting in February, the exhibition moves to Museum Barberini in Potsdam and runs through June 7. If Baden-Baden doesn’t quite fit your plans, Potsdam is an easy alternative, and Berlin is right around the corner

The exhibition catalog is expected by the end of January 2026

Anton Raphael Mengs

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain

November 25, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Anton Raphael Mengs is a name that tends to appear quietly in art history, often overshadowed by the artists he influenced. Yet in the eighteenth century he was a central figure in European art, shaping the foundations of Neoclassicism well before it became an established style.

The Prado presents the most comprehensive overview of Mengs to date. The exhibition brings together 159 works, including 64 paintings, examples of decorative arts, and an extensive group of drawings and works on paper drawn from Spanish and international institutions as well as private collections. This breadth makes it possible to see Mengs not only as a court painter and muralist, but also as an artist deeply engaged with theory and intellectual debate.

Mengs believed that modern art should be grounded in antiquity and in the example of Raphael, while still addressing the concerns of its own time. This balance made his art authoritative in its moment and influential for a younger generation of artists.

The exhibition also highlights Mengs’s impact beyond his own career. His ideas about form, harmony, and artistic ideals shaped artists such as Goya, Jacques-Louis David, and Antonio Canova, even as each adapted those principles in different directions.

Rather than presenting Mengs as a transitional figure, the Prado positions him as a key node in eighteenth-century European art. The exhibition offers a clear view of how artistic thought moved from late Baroque complexity toward the disciplined language of Neoclassicism, with Mengs at its center.

Seeing Silence: The Paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Through April 5, 2026

Before visiting this exhibition, we could not have imagined the impact the work of Helene Schjerfbeck would have on me. She was a Finnish artist we barely knew, and perhaps that unfamiliarity made the encounter even more striking.

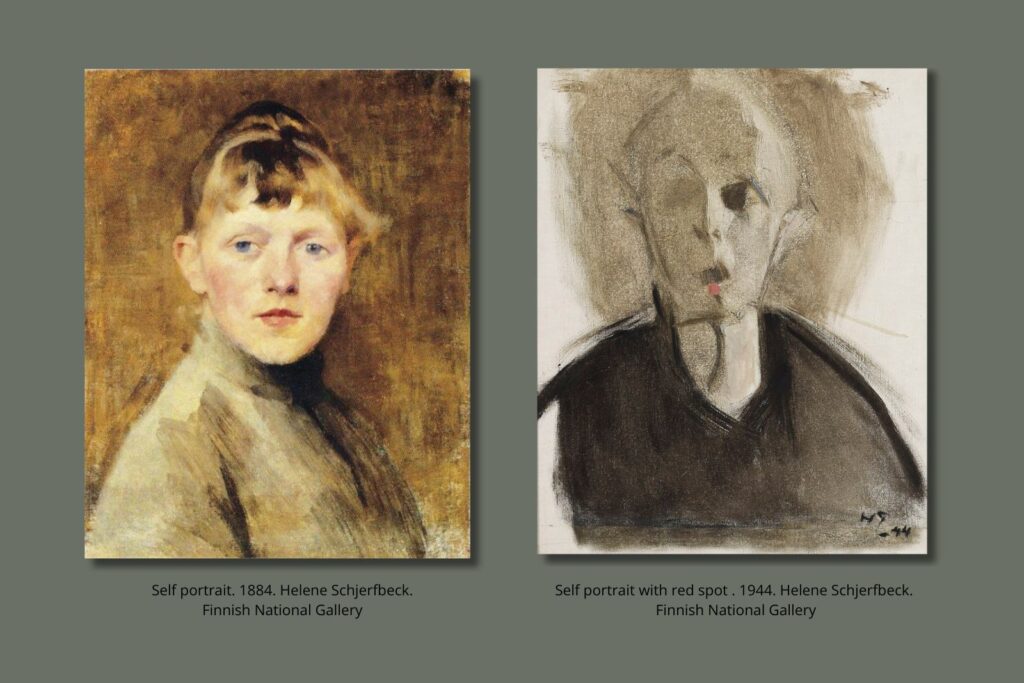

At the heart of the exhibition are portraits and self-portraits. Over the course of her life, Schjerfbeck produced around forty self-portraits, spanning nearly eighty years. Taken together, they read as a continuous timeline that reflects not only aging, but also inner upheaval, illness, isolation, and her forced departure from her home country in 1944. The early works still hold on to likeness and structure, but over time the face begins to fade, simplify, and lose density. In the very last self-portraits, painted just a year before her death, the image almost dissolves. A few quick, sharp strokes, minimal color, and only a faint trace of features remain. These are no longer descriptions of appearance but attempts to register presence.

This restrained and inward-looking approach sets the tone for the exhibition. It is the first major museum exhibition in the United States devoted to Schjerfbeck. Presented at the Met, it traces her path from late nineteenth-century academic painting to the radically pared-down modernism of her later years. As forms grow simpler and the palette narrows, her work becomes increasingly focused and internally charged.

The exhibition is especially powerful for viewers weary of visual noise. There is no effort to impress through scale or technical display. Instead, Schjerfbeck’s paintings ask for time, patience, and a willingness to accept what remains unsaid. Within that quiet space, their strength gradually reveals itself.

The exhibition catalog is expected in the first week of January 2026

Filippino Lippi and Rome

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

November 26, 2025 – February 22, 2026

Filippino Lippi’s name is often introduced as a continuation rather than a destination. The son of Fra Filippo Lippi, a student of Botticelli, he is frequently described as a secondary figure of the Florentine Renaissance. This exhibition in Cleveland quietly but convincingly invites a different view.

Lippi was already well known before he painted his first picture. Born to a celebrated monk-painter and a nun who left the convent, he entered a story that fifteenth-century Florence discussed with no less interest than new altarpieces. This early context, in which religious rules and human emotions collided more closely than was comfortable, set the tone for much of his later work.

The exhibition focuses on Lippi’s Roman period, a moment when his painting changes noticeably under the influence of Rome’s visual environment. Here his works grow more tense and complex. The harmony of Florentine tradition gradually gives way to a nervous line, denser compositions, and imagery charged with a sense of unease.

Around twenty-five works are on view, including paintings and drawings that trace the path from preparatory studies to finished works. The exhibition emphasizes not only outcomes but process, showing how Lippi reworked classical motifs, transformed them, and absorbed them into his own visual language.

This is an intimate exhibition meant to be seen slowly. It does not aim to rewrite the history of the Renaissance, but it offers an important adjustment: to see Filippino Lippi not as a transitional figure, but as an artist for whom Rome became a decisive turning point.

The exhibition catalog is expected in the first week of January 2026

Spanish Style: Fashion Illuminated, 1550–1700

Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York

November 6, 2025 – February 8, 2026

Portraits of kings and queens of the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty have always drawn attention for their distinctive and instantly recognizable dress. In 1623, King Philip IV introduced a law banning ruffled collars as well as fabrics trimmed with gold and silver. This decision marked the emergence of a new visual code associated with the highest ranks of society: the dominance of black color. Over time, black color came to signify restrained elegance and status, and Spanish dress evolved into a lasting visual language of power, faith, and social hierarchy.

Spanish Style: Fashion Illuminated, 1550–1700 invites viewers to look more closely at this language. The exhibition examines how dress and accessories functioned in Spain from the mid-sixteenth to the late seventeenth century, shaping ideas of status, piety, and social order.

Paintings, works on paper, textiles, accessories, and devotional objects from the Hispanic Society’s collection are brought together to show how material and meaning intersected. Particular attention is given to fabric and surface: dense weaves, rigid collars, metallic threads, and heavy folds are treated not as decoration but as carriers of symbolism. Light and texture play as important a role here as cut or color.

The exhibition also traces how Spanish dress was perceived beyond Spain’s borders. Its visual language was widely legible across Europe and often associated with ideals of restraint, moral discipline, and political authority. Fashion thus became a tool through which Spain’s image was shaped both at home and abroad.

The conversation continues beyond the galleries in Spanish Fashion in the Age of Velázquez, a book grounded in the life of Philip IV’s court tailor. Its author, art historian Amanda Wunder, is also the curator of the exhibition. The book shifts attention from the grand portraits of Velázquez to the everyday mechanics of court fashion: the rules, materials, constraints, and choices that shaped the visual code the exhibition invites us to read anew.

Spanish Fashion in the Age of Velázquez: A Tailor at the Court of Philip IV

Modern Art & Politics in Germany, 1910–1945

Albuquerque Museum

August 23, 2025 – January 4, 2026

This exhibition looks at one of the most difficult and fragile chapters in European art history, a period when artistic experimentation in Germany became directly entangled with political upheaval. Between 1910 and 1945, art increasingly lost its autonomy and was subjected to ideological pressure, censorship, and outright bans.

The exhibition traces how artists responded to a rapidly changing world, from prewar modernism and Expressionism to the sober and often unsparing vision of Neue Sachlichkeit. The works reflect not only formal innovation but also growing anxiety, social tension, and a sense of instability that long predated the rise of the Nazi regime.

Particular attention is given to the shifting position of the artist under mounting political control. For some, art became a form of resistance. For others, it led to exile, silence, or persecution. Against the backdrop of campaigns targeting so-called “degenerate art,” painting, drawing, and sculpture emerge not merely as aesthetic objects but as records of interrupted careers and fractured lives.

Rather than offering a comprehensive survey of German modernism, the exhibition draws a clear and uncompromising line. Art does not exist outside history. Here, the works are read as documents of their time, vulnerable, conflicted, and for that very reason, deeply relevant today.

It has been a great year spent with art, and we are grateful to be closing it in such good company. Thank you to everyone who reads us, buys exhibition catalogs from us, or simply reaches out with thoughtful feedback. In a world of digital speed, AI, and constant productivity, taking time to look at a painting made by a human hand feels more special than ever. Take care, keep loving art, and wishing you happy holidays and a wonderful New Year.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

03 Oct 2025

Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages…