Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages people often feared them, imagining that bodies too small or too large disturbed the natural order and carried something of the devil’s mark. With the Renaissance came a new way of looking, growing an interest in the body itself, its anatomy. Difference became part of God’s plan rather than a curse.

At Europe’s royal courts these figures became living symbols of power and wealth. “Dwarfs” could be entertainers, companions, attendants, or even presented as diplomatic gifts, sometimes with secret political roles. Giants usually stood guard, worked as valets, or joined military service.

Their lives were rarely long, and court chroniclers rarely recorded their stories. What survives instead are portraits. Nobles wanted to record the striking looks of their companions, whether in individual portraits or as figures alongside rulers. Those paintings are how we read their stories today.

But the numbers were never even. “Dwarfs” were far more common than “giants”. They were easier to support and seen as more fashionable at court, so portraits of them abound. Giants, by contrast, are rare faces on canvas, exceptions that surprise when they appear.

Double Portrait

The rarest portraits are those that show a “giant” and a “dwarf” together. Perhaps the most famous and striking example is Portrait of Giant Anton Franck and Dwarf Thomele by an unknown artist.

A tall man stands in a ceremonial pink costume, with a sword at his side as a sign of military service, a hat with a white plume in his hand. Beside him is a man of short stature, who at first glance could be mistaken for a child next to the “giant.” He wears a Spanish court outfit, complete with a gold chain and belt, and a small sword with a gilded hilt. This unusual double portrait, painted life-size (8 ft 9 in × 5 ft 4 in), presents us with two court servants of the 16th century who had rare physical features and never actually met in real life.

Archduke Ferdinand II commissioned this portrait from an unknown German artist in 1583. Today the portrait is on view in Ambras Castle, in the enchanting Austrian city of Innsbruck. Under Habsburg rule, Innsbruck became one of Europe’s most important political and cultural centers, and it still preserves its Gothic architecture and medieval spirit.

For a long time, the “giant” in the portrait was identified as Bartolomeo Bona, who served the Tyrolean sovereign Archduke Ferdinand II as a Trabant, or bodyguard. In fact, in some sources online you may still find this portrait listed under his name. The attribution seemed convincing, supported by a wooden statue in armor preserved at Ambras Castle that depicts Bartolomeo Bona. But in 2021, archival documents and visual evidence confirmed that the man in the painting is Anton Franck. And the small figure beside him is none other than Ferdinand II’s favorite court “dwarf,” Thomele.

So let us try to unravel the tangled threads of their lives. And we will begin with the patron who made this portrait possible.

Archduke Ferdinand II and His Collection of Curiosities

Great-grandson, son, and brother of Holy Roman Emperors, and father of a future Holy Roman Empress, Archduke Ferdinand II belonged to one of the most powerful dynasties in Europe, the Habsburgs. First appointed as Governor of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, he later took on the administration of Tyrol and Further Austria. A humanist ruler, he became one of the most influential and celebrated art collectors of his age. His collection, housed at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, was famous even during his lifetime and included art, antiquities, scientific instruments, weapons and armor, musical instruments, and coins. Ferdinand turned Ambras into a Renaissance Museum.

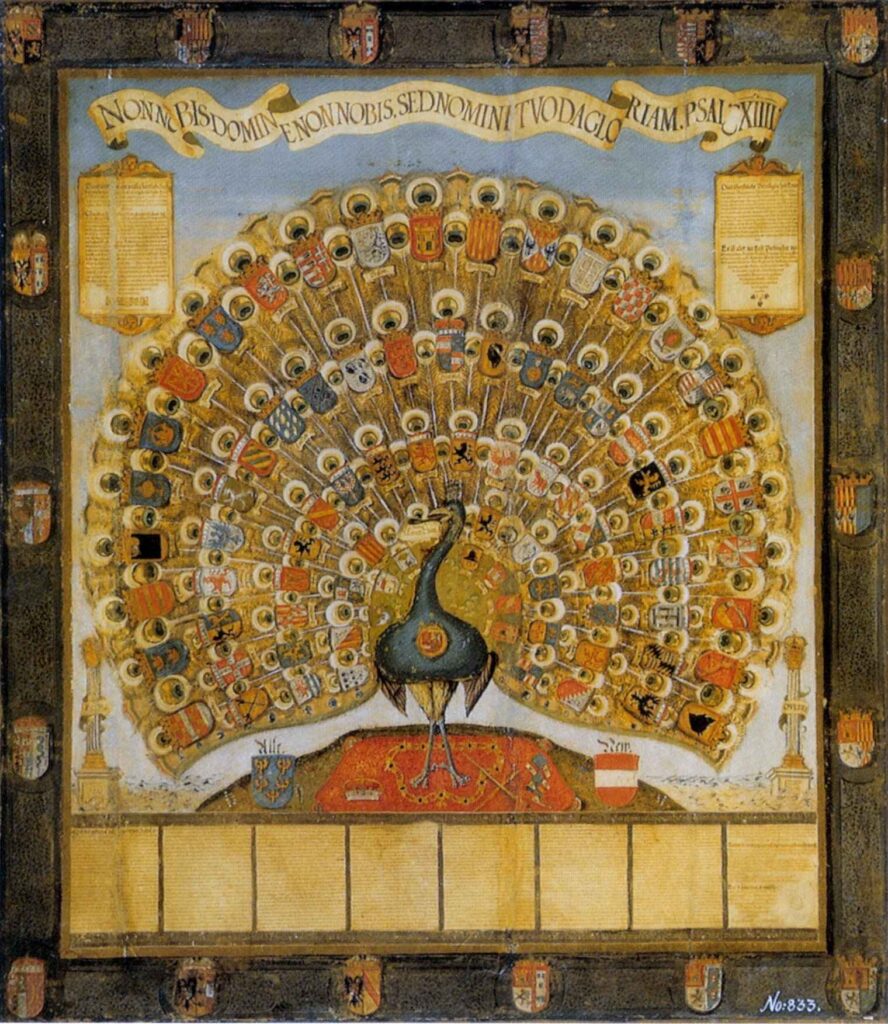

One of the most popular parts of the castle was the Kunstkammer, where visitors could marvel at portraits of extraordinary people: “giants,” “dwarfs,” men and women with unusual physical traits, even individuals covered in hair. Ferdinand personally commissioned many of these portraits, creating a unique collection that survives as Europe’s only gallery dedicated to what were then seen as the wonders of nature and the variety of the human body.

By the second half of the 16th century, princely courts were engaged in what could almost be called a competition of curiosities, vying to secure the smallest “dwarf” or the most astonishing rarity. Ferdinand’s own court included a striking number of “giants” and “dwarfs,” many of whom were presented to him as gifts from noble patrons. According to archival records, one “dwarf” even reached him as a kind of inheritance, passed along from Poland after the death of his sister Katharina, Queen of Poland.

Ferdinand II holds a significant place in the history of art. He is often credited as one of the first systematic collectors. His library’s manuscripts are today recognized on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, and his portrait gallery of the Habsburg dynasty is second only to that of the Spanish royal palace. In 2017, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna marked 450 years since Ferdinand’s rule as Prince of Tyrol with a landmark exhibition that explored every facet of his collecting. The exhibition’s catalog remains a must-have for anyone fascinated by the history of art and collecting.

It was within this atmosphere of fascination for rare physiques that the portrait of Giant Anton Franck and Dwarf Thomele was created. Commissioned for Ferdinand’s collection at Ambras, it stands today as one of the most extraordinary testaments to his vision of a museum that reflected not only power and prestige but also the full spectrum of human diversity.

The Story of Anton Franck (or Franckenpoint)

Ferdinand II never met Anton Franck in person, but he most likely read about him or heard stories through various sources. Given Ferdinand’s passion for collecting curiosities, it is very likely that he wished to include in his collection both the tallest and the smallest people known to him.

Almost nothing is known about Franck’s family or the exact date of birth. Sources disagree on his age, and scholars today place his birth between 1544 and 1561. He came from Geldern in North Rhine-Westphalia and probably left his home in search of a better life. In his youth, he earned his living by presenting himself as a kind of “marvel of creation.” He traveled through Germany and the Netherlands, displaying himself at fairs, inns, and taverns in exchange for food and lodging. This was a common path for people born with extraordinary height, whether “giants” or “dwarfs.”

The first known document mentioning him appeared in the illustrated chronicles of Nuremberg, probably as a type of fairground poster. The inscription read: “Anthonii Franck, born in the land of Gellern, at the age of 14 years. His height is 3 ½ ells. He came to Nuremberg in the year 1575.” If we convert the old Nuremberg ell (about 25.8 inches), Franck’s height at that age was already close to 7 feet 6 inches.

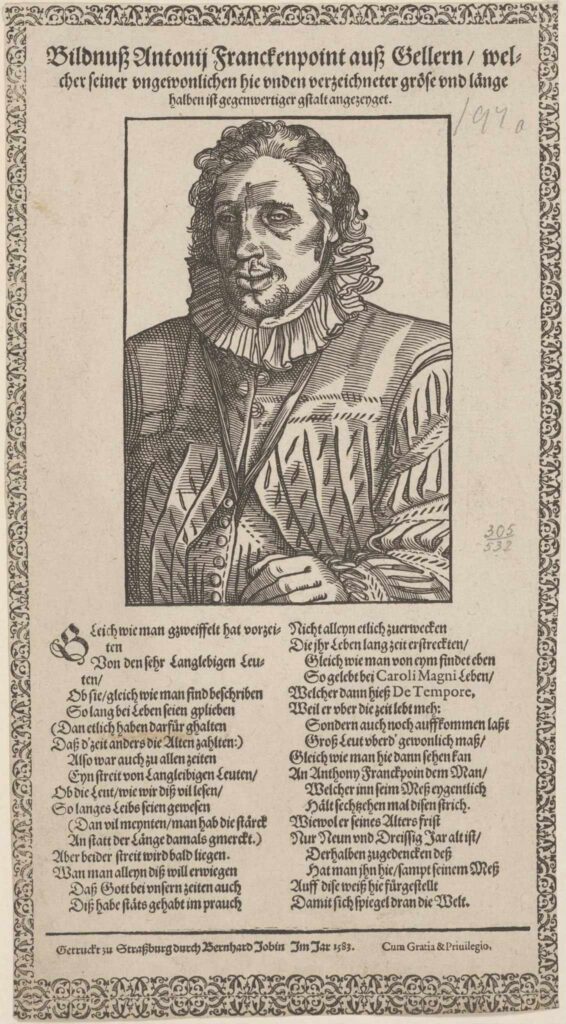

In 1584 he was recorded in Strasbourg, mentioned in local chronicles. Another source is a woodcut included in the physician Johannes Georgius Schenck von Grafenberg’s book The Wonder-Book of Human Marvels and Strange Births. Its heading reads: “Image and portrait of Anthonii Franckenpoint of Gellern, who by right may be counted among the giants and who, because of his unusual height, is here depicted and presented.”

Contemporary accounts also tell of his enormous strength. One chronicle claims he could carry two full beer barrels under his arms. On one occasion a barrel slipped and injured his leg, which may explain the limp confirmed by the walking stick that survives today.

Researchers have also noted a curious detail in his portraits. In several depictions, including the one commissioned by Ferdinand, Franck’s face shows a vertical line from forehead to chin that looks like a scar. On the earliest known image, made when he was said to be fourteen, no such mark is visible. Whether this was a true scar or simply the result of shading remains uncertain. Since the double portrait was probably based on earlier illustrations rather than life sittings, the “scar” may well have been copied from existing prints.

Throughout his travels Franck sought court appointments that would provide stability and income. He eventually found a place at the court of Duke Heinrich Julius of Brunswick-Lüneburg, where he likely served as both guard and personal attendant. What is certain is the date of his death: Anton Franck died at Gröningen Castle on 21 November 1596.

His story did not end there. By order of the Duke his body was dissected by the anatomist Johann Siegfried, and his skeleton was preserved for study at the University of Helmstedt. Later it was transferred to the anatomical collection in Museum Anatomicum, Marburg, where it remains today and is occasionally displayed in exhibitions. That museum also holds a full-length portrait of Franck in a chamberlain’s dress.

Modern scientific studies of his skeleton have provided a kind of medical record for “Tall Anton.” Researchers confirmed that he suffered from pituitary gigantism caused by a benign tumor of the pituitary gland, which led to excessive growth hormone production. His skeleton also shows a fractured femoral neck, severe joint wear, and degenerative changes, which are consistent with the strain of extreme height. It is very likely that in the last years of his life Franck’s mobility was severely limited and every movement caused pain.

The story of Anton Franck, preserved through chronicles, portraits, and even his skeleton, became a symbol of how courts and collectors defined the boundaries of the marvelous. To fully understand the double portrait, however, we must turn to his counterpart.

Thomele, the Beloved Court Dwarf of Innsbruck

Archducal records mention at least nine “dwarfs” who lived at the court of Ferdinand II at various times. Among them, Thomele was the most celebrated.

He was born no earlier than 1560 in Bohemia. His height was about 24 to 28 inches (roughly the size of a six-year-old child), yet his body was well proportioned. That balance of form placed him among the so-called “beautiful dwarfs,” a group especially prized at European courts.

Only a few years ago, scholars combing through the archduke’s account books discovered a detail that gave Thomele a full identity. Ferdinand invited the boy’s father to visit him and personally covered the cost of travel and lodging. These entries reveal that Thomele’s real name was Thomas Kaiser. They also confirm that the archduke’s personal tailor sewed his clothing, a sign of the special favor he enjoyed at court.

Thomele’s fame truly began in 1568, during the wedding banquet of Ferdinand’s nephew. When a grand pie was carried into the hall, Thomele suddenly leapt from it, dressed in armor and carrying a small sword. After greeting the bride and groom, he danced across the banquet table. The spectacle caused such delight that it was repeated at other feasts with other “dwarfs.”

Following the event, four portraits of Thomele were commissioned. Three are now lost, but one survives. In that painting, he wears the very armor from his unforgettable pie-jumping performance. The surviving portrait of Thomele is kept at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, but unfortunately, it is not accessible even through their digital archive. Since we cannot show you the painting itself, we can at least share the next best thing: his actual armor, still preserved at Ambras Castle and displayed beside a wooden statue of the court “giant” Bartolomeo Bona.

Thomele also lived on courtly anecdotes. One tale describes how a “giant” mocked him for his small stature. Seizing an opportunity for revenge, Thomele deliberately knocked Ferdinand’s gloves to the ground. By etiquette, the tall courtier behind the archduke was obliged to retrieve them. As the man bent down, Thomele darted forward and slapped him twice across the face.

Stories like these, full of wit and spirit, made Thomele a folk figure in Innsbruck. A fresco created in 1566 on one of the city’s medieval buildings still shows his likeness, ensuring his memory endured in public view.

Thomele died in 1588 at the age of 28. The cause of death is unknown, but his funeral expenses were paid directly by Ferdinand II, a final mark of the archduke’s favor.

Ambras Castle: A Renaissance Cabinet of Curiosities

A visit to Ambras Castle is the kind of experience that stays with you for life. Here you can meet the “dwarfs” and “giants” of courtly culture and see the only known portrait of Vlad Țepeș, better known to most of us as Count Dracula. We are sure you’ll find yourself standing still for a long time in front of the haunting Portrait of a Disabled Man or pausing at the legendary “hairy family” of Pedro Gonzales.

Don’t miss the Spanish Hall, one of the most beautiful Renaissance halls in Europe, built in the 1570s and decorated with larger-than-life portraits of Tyrolean rulers, mythological figures, and painted illusions that make the space shimmer with life. And remember to look up, because the coffered ceilings and fresco details hold wonders you might otherwise miss. Give yourself some extra time outside too, since the peacocks wander around as if they own the place. Take it from us, they are almost impossible to photograph without a little chase. Every corner of this castle has a story, and that is exactly why it is worth a visit.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

28 Aug 2025

Vittore Carpaccio’s Lion of Saint Mark: Venice’s Symbol in the Doge’s Palace

In Venice, the Doge’s Palace stood as the stage of a thousand-year republic. Its…