Portraits of Power: Gentile Bellini Between Sultan and Doge

From the Doge’s Hall to the Sultan’s court, Gentile Bellini’s portraits tell a story of fragile peace, political power, and an artist bridging two worlds with his brush.

Venice and Ottoman Empire: A Precarious Peace

The history of Venice and the Ottoman Empire was a constant push and pull between war and trade. Two maritime powers fought bitterly for control over the Mediterranean and its routes, only to strike deals and exchange lavish gifts afterward. The Treaty of Constantinople of 1479, signed by Doge Giovanni Mocenigo, ended one of the most exhausting wars with the Ottomans. For Christendom, however, this peace felt less like a victory and more like a humiliating concession: Venice agreed to pay tribute and yield strategic territories, clinging desperately to its influence and trading privileges in the Eastern Mediterranean.

It was in this fragile time of diplomacy and uneasy compromise that the story of three portraits by Gentile Bellini began, one left unfinished, one lost and rediscovered, and one finally completed.

An Interrupted Commission

In 1478, Giovanni Mocenigo became the Doge of Venice, the highest office of the Republic. By tradition, a formal portrait of every Doge was commissioned and hung in the Hall of the Great Council in the Palazzo Ducale, Venice’s pantheon of power. A curious custom: should a Doge commit treason, his portrait was painted over with a black square bearing the inscription of his disgrace. Our story, thankfully, involves no treason, but it is no less dramatic.

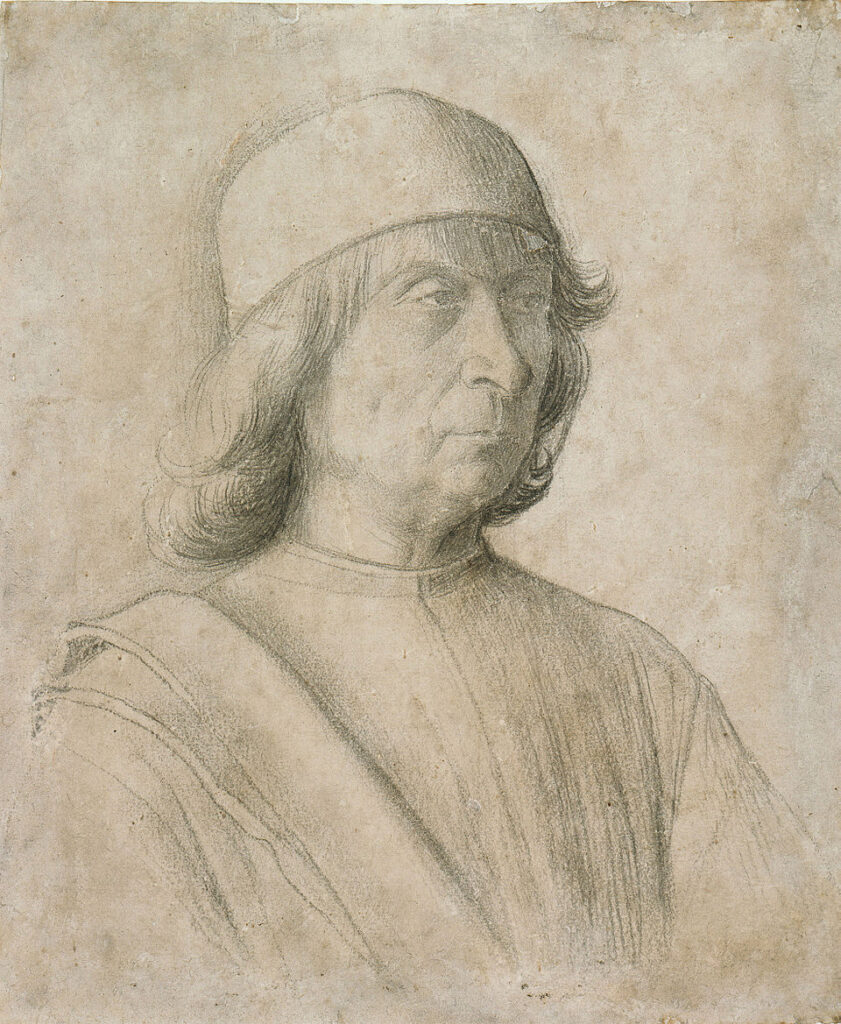

Gentile Bellini, elder brother of the great Renaissance master Giovanni Bellini, was himself renowned as a portraitist and a skilled diplomat. As the official painter of the Republic and court artist to the Doge, Gentile was commissioned to portray the new ruler. But in 1479, his work was suddenly interrupted: the golden background remained bare, the ceremonial corno ducale (the Doge’s ceremonial headdress) only sketched. The Senate ordered him to drop his brush and leave Venice for Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), on a mission to secure the fragile peace with Sultan Mehmed II.

The Sultan’s Portrait and Its Mysterious Journey

Sultan Mehmet II, conqueror of Constantinople in 1453, ended a thousand-year Byzantine Empire at the age of just 21. Young, bold, highly educated, and a passionate lover of the arts, especially Italian painting, he built a cosmopolitan court where Greek scholars and Persian poets gathered freely. Though a Muslim ruler, he collected Christian art, fascinated by its beauty and prestige. After Venice’s defeat, Mehmed sent an emissary to the Senate requesting a skilled artist for his court. Gentile Bellini sailed east not only as a painter but as a diplomat for his Republic’s most vital trade partner.

In 1480, Bellini painted what is often referred to as the first European portrait of a Turk, painted from life, an unprecedented act of cultural diplomacy. An Ottoman sultan, breaking Islamic figurative conventions, chose to be depicted like a Renaissance prince. For Mehmet, this may have been a self-portrait of power: a way to project himself to Europe as an enlightened monarch.

But when Mehmed died in 1481 (some say poisoned), his son Bayezid II enforced stricter religious policies. The portrait of his father was officially deemed improper and, while it should have been destroyed, it was most likely sold off instead. Historian Franz Babinger, a biographer of Sultan Mehmet II, speculated that Bayezid liquidated his father’s European art collection, leading to a curious note that appears in later catalogues: “sold at the bazaar.”

The painting disappeared for nearly four centuries, resurfacing only in 1865, when British diplomat Sir Austen Henry Layard bought it in Venice from a family who claimed they had received it as payment for a debt. Today, this extraordinary survivor, a fragment of diplomacy on canvas, belongs to the National Gallery in London (on loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum until 2027), a witness to a fleeting moment when East and West dared to look each other in the eye.

The Doge’s Completed Portrait

By mid-1481, Mehmet II was dead, and with him ended that rare window of diplomatic experimentation where a sultan would sit for a Venetian painter. Returning to Venice, Gentile Bellini painted a new, formal portrait of Doge Mocenigo: tempera on poplar, presenting the ruler in strict profile, shown wearing ceremonial robes and the iconic corno ducale, its ornament painted with jeweler’s precision. The gaze is calm, immovable, the dignified face of Venetian power, finally secured for posterity.

This panel passed through the hands of eccentric British collector William Beckford, his daughter the Duchess of Hamilton, and art historian Langton Douglas, before entering the Frick Collection in 1926.

For decades, the sitter was misidentified as another Doge, Andrea Vendramin. Only painstaking comparisons with medals and frescoes restored the name of Mocenigo. This became one of the earliest cases of analog facial recognition in art history.

The Final Brushstrokes of History

We do not know whether Doge Giovanni Mocenigo ever saw his final ceremonial portrait. He died of plague in 1485, leaving Venice in mourning and Gentile Bellini without another powerful patron.

The painter outlived both great sitters of his life – the Sultan, whose portrait vanished in the turbulence of political change, and the Doge, whose portrait was likely finalized only near the end of his life. Gentile Bellini’s legacy would prove fragile: in 1577, a devastating fire in the Palazzo Ducale destroyed countless masterpieces, including some of his works, leaving empty spaces where once the faces of Venetian rulers had gazed down.

Three portraits, three faces of power, three different fates: the unfinished profile of Mocenigo, now in the Museo Correr in Italy, a thread cut short by eastern diplomacy; the completed ceremonial likeness in New York, Bellini’s final word on Venetian authority; and the long-lost portrait of Mehmet II, slipping out of the Ottoman Empire and preserving the memory of a rare moment when East and West dared to look one another in the eye.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

03 Oct 2025

Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages…