The Art of the Nightmare at the the Musée Marmottan Monet

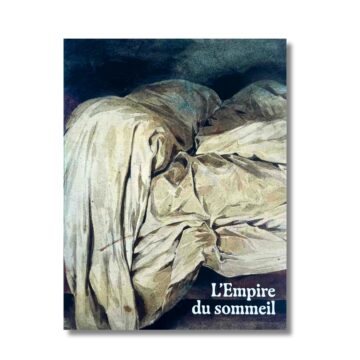

Sleep and nightmare, sleep and desire, sleep and death. The Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris is currently hosting a wonderfully curious exhibition, The Empire of Dreams. It brings together 19th- and 20th-century paintings alongside thematic objects from antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the modern era. The result is an eclectic, multilayered experience, much like the nature of sleep itself.

Among the strangest figures to wander through the mythology of the night is the incubus. A small, unsettling creature, it first entered the visual arts through Henry Fuseli and later resurfaced in powerful new forms, and artists like Ditlev Blunck would later return to the image with their own visions. But before we get to that, let us start with the central figure of this nightmare.

Incubus or Mara

To understand why this strange figure keeps appearing at the foot of the bed in paintings across different eras, we need to go back to the beginning. Many European traditions speak of nocturnal spirits that “come” during sleep, sit on the chest, and provoke terrifying visions. Sometimes they’re called an incubus, sometimes a mara, and just to complete the picture, we should add the succubus as well. So who is who in this little demonological hierarchy?

The Mara is a folkloric ancestor of all “nightmares.”

In Germanic, Scandinavian, and Slavic traditions, the mara is a night spirit who presses on the chest of a sleeping person and brings on the state we would now describe as sleep paralysis, that strange moment when the body is caught between REM sleep and waking. You are both asleep and not asleep, aware but unable to move a muscle. According to legend, the mara sends vivid, frightening dreams and often appears as a female figure with the ability to change her form. It’s most likely from this tradition that the English word nightmare ultimately emerged.

The Incubus, by contrast, belongs to a later Latin tradition and to Christian demonology.

He is also a nocturnal visitor who “sits on top,” who presses, who triggers fear and suffocating dreams, but unlike the mara, the incubus has a clearly defined erotic agenda in the theological texts. His Latin name incubare literally means “to lie upon.” The incubus is described, categorized, and fully integrated into medieval theological systems.

In the Middle Ages, the incubus was equated with the devil, and church writings used the term specifically to describe the heresy of engaging in sexual relations with a demonic being.

Remember Merlin, the wise magician from Arthurian legend? In the story, a demon-incubus attempts to create an “anti-Messiah” by conceiving Merlin with a devout woman. The plan fails: the mother clings to her faith, the infant is baptized, and evil loses its claim. Here the incubus appears as a classic demon of Christian iconography.

Tradition also distinguishes the succubus, the female counterpart of the incubus, a demoness who seduces men in their sleep. But in art, these figures often blur together. What matters is not gender or fine points of theology, but the intrusion itself , the breaking of the boundary between a person and the depths of their own unconscious.

Füssli’s Incubus: Nightmare or Private Obsession?

The creature that Füssli placed at the center of his most famous painting, The Nightmare, is described in different sources as either an incubus or a mara. It is one of those works that refuses to settle into a single interpretation. The painting blends erotic tension with fear, theatricality and a kind of clinical fascination with the nocturnal mind. Sigmund Freud would have called that mind the subconscious, and it is said that a reproduction of this painting hung in his apartment in Vienna.

The woman lies in a pose that resembles sleep paralysis. Her body is relaxed, her head tilted back. The demon sits on her chest, and from behind the curtain a large, almost surreal horse’s head peers into the scene. It is no surprise that the visual language of this painting has been viewed as an early step toward surrealism. In eighteenth century English the word nightmare carried a double meaning: mare in its older sense referred to a night demon who brings terrifying dreams, while the familiar everyday meaning of mare was simply a female horse. The horse’s head can be read as a visual pun, although perhaps it is nothing more than an image from the woman’s dream. Füssli seems to invite multiple readings and subtle jokes layered inside the composition. One theory proposes that the frightening horse’s head was inspired by the horse in Salvator Rosa’s The Shade of Samuel Appears to Saul.

The figure of the sleeping woman may also have come from another source. Many scholars have noted the strong resemblance between her pose in The Nightmare and the pose of Dido in Reynolds’s The Death of Dido. Both paintings were created in the same year, and the artists were well acquainted with one another, which makes the possibility of visual borrowing entirely plausible. The similarity between the two reclining figures is striking.

But Füssli hid one more secret inside this work, and it has troubled art historians for a long time. On the reverse side of an early version of The Nightmare he painted an unfinished portrait of a young woman who is believed to be Anna Landolt. Füssli was in love with her, deeply and unhappily, and struggled with the news of her engagement to another man. Some researchers see the painting as a kind of confession: a mixture of anguish, longing and the weight of unfulfilled desire. In this reading the incubus becomes a metaphor for impossible love, and the entire scene moves from fantasy into the realm of emotional self-portrait. The painting becomes part of Füssli’s own story, a record of his personal “night obsession.”

Whatever Füssli intended, whether an imaginative experiment, a study of the subconscious or a private tragedy, the moment The Nightmare was shown to the public it made him famous. The image was reproduced widely not only in England but throughout Europe and the United States. The incubus crouched on the woman’s chest became so compelling that it inspired countless copies, homages and caricatures. Even today it remains the most recognized visual embodiment of a nightmare in the history of art.

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare is not part of the exhibition The Empire of Dreams at the Musée Marmottan Monet. The show focuses exclusively on works from European museums and private collections. Fuseli’s painting can instead be seen in the permanent collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, where it remains one of the museum’s most iconic works.

What the Paris exhibition does include is another work inspired by Fuseli’s famous scene: The Incubus Leaving Two Sleeping Women.

It was painted about a decade after his original nightmare. The work lacks the unsettling realism of The Nightmare, yet it contains a fascinating detail. The central figure, the woman startled awake from a dream shaped by the incubus, is unmistakably the same young woman who appears in Fuseli’s original composition. The second woman in the scene, according to several art historians, is believed to be a self-portrait of Fuseli himself.

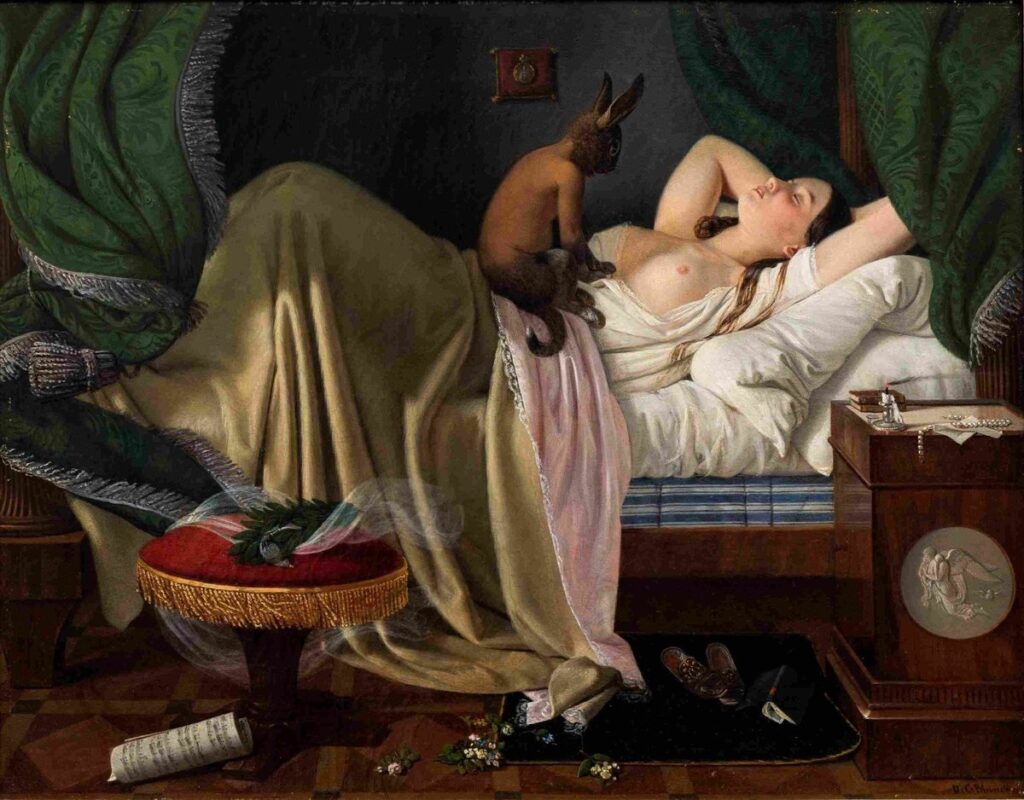

Ditlev Blunck’s Nightmare

If Füssli turned the incubus into an allegory of fear, Ditlev Blunck approached the theme with far more boldness and far more provocation. He was born in Germany but became part of what is now known as the Golden Age of Danish painting. Even so, he remains one of the more controversial figures in Danish art and is often grouped among the so-called “forgotten artists.” His biography includes an expulsion from Denmark in 1841 after being charged with “sodomy” under the criminal code of the time. Many Danes also have not forgiven him for siding with the German forces in the Schleswig-Holstein conflict, a war that set Denmark and Germany against one another. Whatever one thinks of his life, it is Blunck’s painting that stands out as the most daring interpretation of the nightmare motif after Füssli.

Blunck’s Nightmare is included in the Marmottan Monet exhibition, and it is nearly impossible to pass it without stopping. His incubus bears none of the dark charisma or “meme-like” familiarity that clings to Füssli’s creature. Here the demon is a hybrid with a rabbit’s head, a man’s torso and the hind legs and tail of a cat. The realism makes him especially disturbing.

The scene feels like a small stage. The canopy is drawn back like theater curtains, the incubus crouches on the bare chest of a sleeping woman and she remains completely unaware of him. Her body is loose, her lips slightly open, and her posture suggests something closer to sensual drifting than fear. Here the nightmare and the pleasure fold into each other and create a mood that is both uneasy and strangely alluring.

Blunck touches on a theme his century knew well, the gap between respectable bourgeois ideals and the far less disciplined world of human desire. On the floor lies a crumpled sheet of music, the kind of practice piece young women were expected to master as part of their proper upbringing. Lessons, exercises and endless refinement were meant to prepare them for society. In this room the sheet has simply been pushed aside. A book lies face down on the carpet, a small hint that study and social expectations have slipped behind more instinctive urges.

There is another detail worth noticing. The bedside table is decorated with a drawing based on one of the most popular marble reliefs by the Danish-Icelandic sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, Night. The winged female figure is accompanied by an owl and carries her sleeping children, Sleep and Death, across the sky. Poppies woven into her hair evoke the ancient association with sleep-giving plants. Through this reference Blunck places the traditional iconography of Night, with its promise of rest, inside a room where that promise is broken by a supernatural intrusion.

The exhibition The Empire of Dreams in France offers a rare chance to see how nineteenth and twentieth century artists explored the night, the unconscious and the threshold of another world. If a trip to Paris is not in your plans this season, we have the exhibition catalog, and its more than two hundred pages offer a fascinating journey through the art of sleep.

Header Image credits:

This collage was created by the author using details from the following artworks:

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (1781, Detroit Institute of Arts); The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (1790-1791, Goethe Haus); Nightmare by Nikolai Abildgaard (1800, Sorø Art Museum); The Nightmare by William Raddon (1827, Victoria and Albert Museum); Nightmare by Ditlev Blunck (1846, Nivaagaard Museum)

The original artworks are in the public domain or shared under the licenses indicated above.

The collage composition © 2025 exhibitioncatalogs.com. All rights reserved.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

03 Oct 2025

Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages…