Trolls, Death, and Tender Monsters: The Magical World of Theodor Kittelsen

Have you ever smiled at a sea monster or felt sorry for an old lady carrying the plague? Welcome to the magical world of Theodor Kittelsen, where trolls, death, and tenderness walk hand in hand.

Can You Paint a Monster with Love?

At first glance, Theodor Kittelsen’s The Sea Monster seems to leap straight out of a nightmare: a hulking, moss-draped figure rises from the waters, gaping mouth wide open, wild eyes staring.

You should be afraid. But then, you are not. Instead, you find yourself smiling. Because somehow, impossibly, Kittelsen has made his monster… lovable.

The creature looks less like a threat and more like someone who stumbled out of a bad hair day at the bottom of a lake. With strands of green seaweed hanging from his head like a child’s forgotten Halloween costume, he seems more bewildered than menacing, a lost soul who never got the memo that he was supposed to be terrifying.

Kittelsen had a rare gift: he could paint the grotesque with tenderness, the terrifying with a wink of humor. The Sea Monster is a perfect example.

It is not just a creature of fear – it is a creature of sympathy, curiosity, and even ridiculous charm.

Because maybe, just maybe, monsters are not meant to be hated. Maybe they just need a warm smile… and a towel.

Meet the Man Behind the Monsters

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914) was many things: a painter, graphic artist, illustrator, caricaturist, and storyteller. But above all, he was a dreamer. A one who never quite grew out of seeing magic hidden in his beloved Norway’s forests, mountains, and fjords.

He studied art in Munich, where the serious, academic painting style of the day mostly bounced off him like rain on a troll’s back. Kittelsen had his way of seeing the world, one where monsters had bad posture, princesses picked lice from trolls, and even Death herself, the old woman Pesta, shuffled across the countryside with a broom in hand.

It was through illustrating Norwegian folk tales that Kittelsen truly found his home. His drawings did not just decorate the stories; they became the stories, embedding themselves into Norway’s cultural memory.

Today, when we picture trolls – big-nosed, moss-covered, strangely shy – we see Kittelsen’s trolls.

His art was never about terrifying audiences. It was about inviting them into a parallel world that lived just a few steps to the left of reality, a world filled with wonder, melancholy, mischief, and the occasional seaweed-soaked monster in need of a friend.

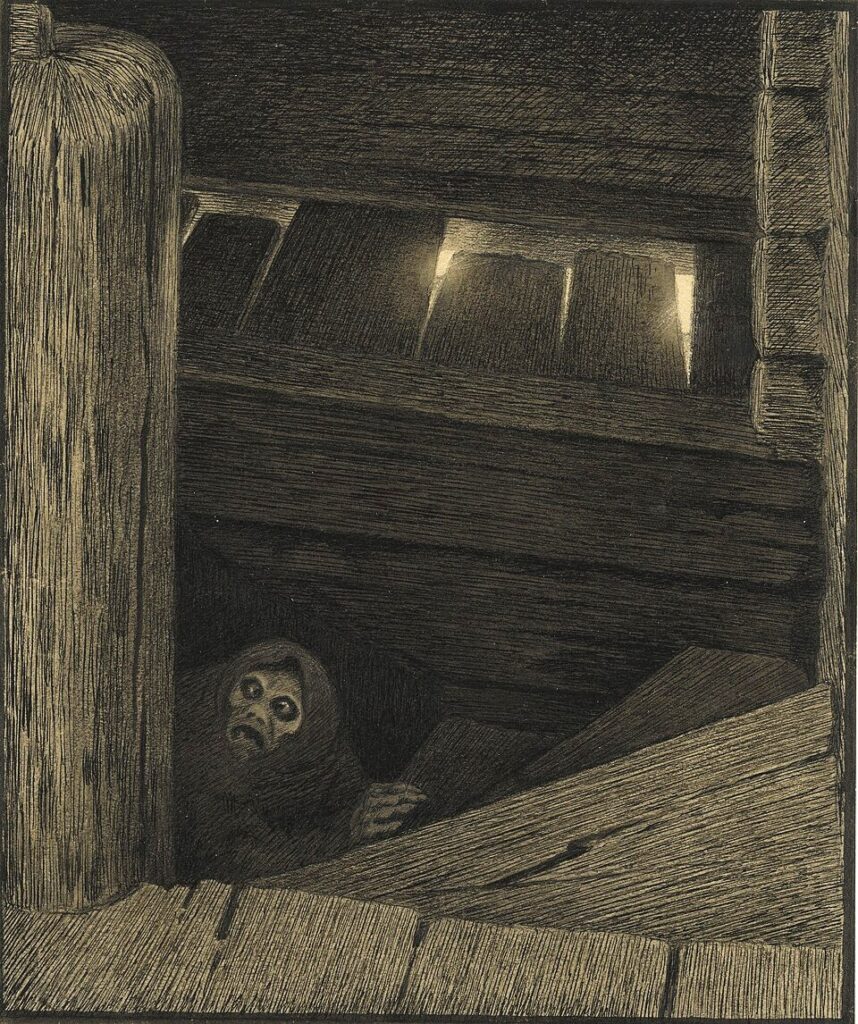

When Death Comes Creeping Upstairs

In Norwegian folklore, Pesta is the personification of the Black Death that devastated Norway in the 14th century. She appears as an old woman dressed in black, carrying either a broom or a rake. It was said that if Pesta came with a broom, she would sweep everyone in the house into death; if she carried a rake, some might survive. This grim figure became deeply rooted in the national imagination, a lasting symbol of fear and inevitability.

But look at how Theodor Kittelsen paints Pesta.

In Pesta on the Stairs, Death does not burst through the door with drama or grandeur. Instead, she creeps up a dark wooden staircase, small, frail, almost embarrassed to be herself. Her face is pale and childishly sad, her back hunched under the weight of the sorrow she brings. Pesta does not roar or rage. She does not threaten. She simply climbs – slow, almost apologetic, like a guest who wishes she did not have to deliver such terrible news, but must do it anyway.

In the hands of another artist, this scene might have been grand and theatrical. But Kittelsen understood something deeper: that the scariest visitations are the quiet ones, those that slip through the door, ascend the stairs, and settle into your dreams without a sound.

Even when painting the embodiment of the Black Death itself, Kittelsen reminds us: sometimes the greatest fears do not roar, they whisper.

Of Trolls, Beheadings, and Hair Care

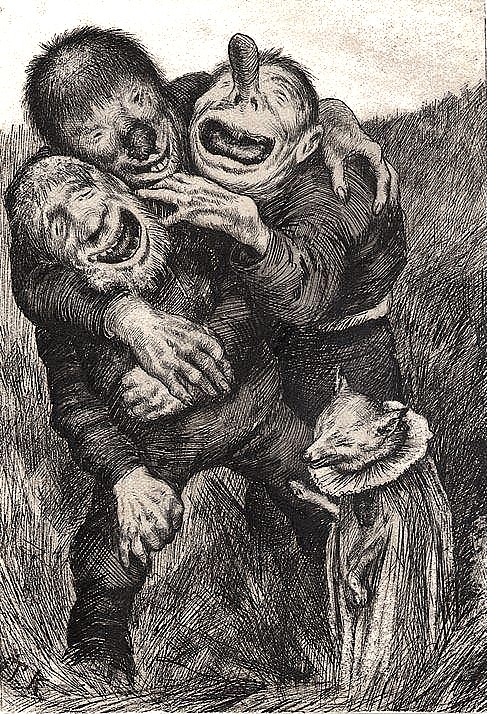

In Kittelsen’s world, trolls are everywhere. They lurk in forests, wallow in rivers, lumber through misty hills, often with a tragic lack of self-awareness and a hairstyle that would make even the bravest princess reach for a comb.

Sometimes, he painted trolls at their most dramatic, like in The Ash Lad Beheads the Troll, where the hero swings a sword with triumphant determination and the troll crumples in theatrical despair.

Even here, Kittelsen cannot help but stir a flicker of sympathy for the poor defeated giant.

Then there are glimpses of everyday troll life, like in The Pleasure of Having Children, where two scruffy troll kids bicker and bond, all tangled hair, and dirty feet, wild, chaotic, and strangely endearing.

And finally, The Princess is Picking Lice from the Troll is the purest example of Kittelsen’s tender, whimsical vision.

A princess sits patiently, tending to a gigantic troll like a nursemaid gently combing out a child’s hair. The troll slouches in trust, humble, almost bashful, under her care.

It is a scene that should not exist, and yet it feels more real, more touching, than many grand heroic tales. In Kittelsen’s hands, even the monstrous deserved a little grooming, a little grace, and a little kindness. Because maybe kindness, like storytelling, bridges the space between fear and familiarity.

The Quiet Magic of Theodor Kittelsen

Theodor Kittelsen did not just illustrate folk tales, he gave Norway a mirror to its own dreams.

Through trolls, lonely monsters, sorrowful Death figures, and shy forest creatures, he built a world that feels at once ancient and intimately familiar.

Today, most of his works are carefully preserved as part of Norway’s national heritage, lovingly kept at the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo. They remind us that storytelling is not just about words, it’s about seeing, feeling, and remembering.

And perhaps Kittelsen’s art whispers one last quiet truth, that even the strangest monsters, even fear itself, become a little less frightening when you meet them with tenderness and humor.

Although Theodor Kittelsen is deeply revered and beloved in Norway as a national artist, you will be hard-pressed to find a proper catalog of his work or any substantial publication devoted to his art outside of Norway. His lack of global recognition means he is often overlooked in registers of the world’s most renowned painters, a quiet gem hidden within Norway’s cultural heart.

But we believe that one day, we will be able to offer you a beautifully illustrated volume that brings the enchanted, melancholic, and mischievous world of Theodor Kittelsen into your hands.

Exhibition calendar

21 Aug 2025

Letters, Games, and Saint Fools: The Art Exhibitions of August 2025

August is usually a sleepy month in the art world. Museums are busy plotting…

Art news

28 Aug 2025

Vittore Carpaccio’s Lion of Saint Mark: Venice’s Symbol in the Doge’s Palace

In Venice, the Doge’s Palace stood as the stage of a thousand-year republic. Its…