Pass the Dice: Jan Van Hemessen’s Marriage Code

The exhibition Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks, organized by The Phoebus Foundation in collaboration with leading museums across North America, is a true triumph of Flemish art.

After traveling through Denver, Salem, Dallas, and Montreal, it now concludes its journey in Canada, at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where it will remain on view until January 18, 2026. This is more than a gathering of masterpieces. It is a philosophical stage play where faith meets sensuality, sin meets virtue, and irony meets power.

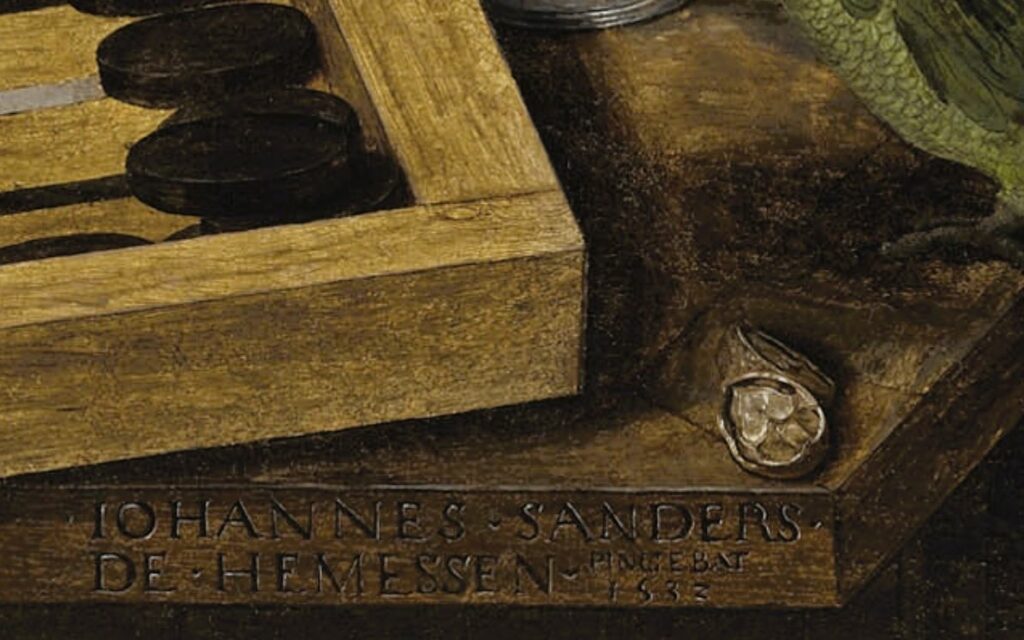

Among its most enigmatic works, in our view, is Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Portrait of a Couple Playing Trictrac (1532).

This is one of the earliest pair portraits in Flemish painting to be executed on a single panel (until then, couples were typically painted on two separate boards). The couple, clearly dressed for success, is engaged in a game of trictrac. To one side of the painting lies a plate of fruit; to the other, a glass of wine, walnuts, and a parrot.

At first glance, everything seems perfectly proper. There are no grotesque grimaces, those hallmark, vice-exposing flourishes so favored by Hemessen, no overt symbols pointing to moral corruption. Nevertheless, a faint veil of mystery runs through the entire scene, as if something does not quite add up, as if the painter is inviting us to play along in a quiet guessing game: who, in truth, are these sitters? Saints… or sinners?

In this article, we will try to decode Hemessen’s game of hints and symbols by reading it through the visual language of the period, and see if we can uncover what the artist truly meant to tell us.

Trictrac: The “Eleven” Gambit

The game board is the first thing to catch your eye in the painting. It all but spills into the viewer’s space, as if inviting us to sit down for a round. But do not be too quick to roll the dice. The game here is not as straightforward as it seems.

The word trictrac was one of the names for backgammon used in Flanders. The game had been popular long before it ever found its way onto canvas, but in early 16th-century art it appears only rarely. In the northern tradition, games of chance were a slippery slope.

Hemessen’s work is one of the earliest and perhaps the clearest examples of the game shown in an intimate, domestic setting. The only close contemporary parallel is Backgammon Players from the circle of Lucas van Leyden.

Although that scene is far from homey: the hapless player, likely lured into a brothel, is surrounded by treacherous women. Right beside his female opponent’s hand lie coins and playing cards, a clear hint at a rigged game and a trap ready to spring. The atmosphere speaks of deceit and vice far more than innocent recreation.

Scenes of trictrac in prints and genre painting only become common in the 17th century, and rarely at the family table. The setting shifts to taverns and brothels, where the game becomes a backdrop for quarrels, heavy drinking, and shady dealings.

Take Jacob Matham’s engraving The Devil in a Brothel: here, dice and counters fly along with chairs, the match descends into chaos, and a drawn knife makes it clear that the evening will end in something far worse than a lost bet. Such negative depictions multiply in the 17th century, with backgammon turning into a favored symbol of wasted time, idleness, and sinful behavior.

And if you look closely at Hemessen’s painting, you will notice a small but telling detail: the dice on the board show a five and a six, making eleven.

In the visual culture of the early modern period, numbers were rarely just numbers. They often carried allegorical, moral, or cautionary meaning. Ten stood for order and law – the Ten Commandments. Twelve was completeness and harmony – the apostles, the months of the year, the zodiac. Eleven broke the pattern: a sign of excess, of transgression, of stepping beyond the bounds of what is permitted. In the Northern Renaissance visual code, it was easily read as temptation, a breach of moral order, the start of a fall from virtue.

Hemessen, a master of genre scenes with moral undercurrents, surely did not leave this combination to chance. The game board becomes a cipher suspended between virtue and vanity. The match may look innocent enough, but the dice are already whispering: there is more at stake here than just a game.

The Fruit Cipher

Before the 17th century, still life had not yet emerged as an independent genre in painting. Depictions of fruit, vegetables, flowers, and household objects appeared mainly as secondary elements within religious or genre scenes and almost always carried symbolic meaning.

One early example of an emerging still life, still inseparable from its religious context, is The Holy Family by the Netherlandish painter Joos van Cleve.

Painted after a work by Jan van Eyck, it features exquisitely rendered fruit in the foreground. But this is not abundance for the sake of abundance. Each fruit carries a theological subtext. Such imagery in the late 16th century functioned more as a visual prayer than as a scene meant to whet the appetite, inviting contemplation, not consumption.

It is within this framework, when fruit on paintings still served as symbols of good and evil or virtue and sin, that we should view the still life in Hemessen’s work. Here, the fruit is not mere decoration, but a kind of code hidden in the produce. On the plate before us lies almost a complete moral alphabet of fruit – apples, grapes, cherries, pears, and, most notably, a sliced quince.

The apple recalls Adam and Eve, original sin, and temptation. Grapes can allude both to Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and revelry, and to the wine of the Eucharist, especially when paired with a glass of wine beside the woman. Cherries in iconography are often linked to the Garden of Paradise, innocence, and purity, yet in certain contexts may also hint at seduction. Pears, in religious symbolism, represent mercy or virtue, while in secular imagery, their shape and associations could render them an erotic emblem. The sliced quince, according to the Northern Renaissance visual culture, symbolizes marriage and fertility, often found in wedding still lifes. It is perhaps the clearest visual clue that we are looking at a couple, likely recently married.

But if quince frames the pair as virtuous newlyweds, the walnut is a true double agent.

In Ancient Rome, it symbolized a strong marriage. In Christian tradition, it was an allegory for the threefold nature of Christ: the shell representing his suffering, the inner skin his humanity, and the kernel his divinity.

But in a more worldly, even playful reading, the walnut could also signify temptation. Look at two paintings by Jan Steen, The Tired Traveller and Le repos devant l’auberge (Rest Outside the Inn). The compositions are nearly identical: a young woman offers refreshment to a traveler. In one, a rose, the symbol of seduction, sits on the table. In the other, it is replaced by cracked walnuts. These are no mere snacks; they refer to an old Dutch proverb:

“Wie de noten kraken wil, moet ze breken» – Who wants the nut must crack it. In modern terms: “seize the opportunity.”

And in this context, the opportunity is hardly innocent. As the Musée Fabre, which holds one of the paintings, notes: “Here, the traveler will likely attempt to seduce the maid offering him a drink.” Why Steen replaced the overt symbol of the rose with walnuts is unclear. But painters of the Northern Renaissance delighted in turning their works into riddles. No glass of wine, no cherry, no walnut appeared on their canvases by chance. The North distrusted the obvious. It spoke in codes.

Could Hemessen, as early as the mid-16th century, have played with such ambiguity? Most art historians read the walnut in his painting strictly as a religious symbol. But painting is not catechism, symbols can slide between meanings. And if the entire composition walks the tightrope between virtue and temptation, why should even an innocent walnut not play a double role?

Who Said Ave: Parrot in Art

What is a blue-fronted Amazon parrot from the tropics of the New World doing in a Flemish portrait of the 1530s? He is clearly not a local.

By the sixteenth century, after Columbus and all those who sailed in his wake, this bird had already found its way into the homes of wealthy families in the Dutch Republic and the Southern Netherlands (in what is now Belgium), a mark of affluence, far-reaching connections, and a taste for the exotic. But our feathered friend is more than a decorative prop. Here, he is a quiet observer, part of the household, and at the same time, a small but significant player in a moral riddle.

In painting, the parrot was no longer merely a trophy of travel. Its symbolism was far richer.

Herald of Heaven, Companion of the Virgin Mary, or Symbol of Paradise

In Christian iconography, the parrot is a singular creature, often depicted as a faithful companion of the Virgin Mary. The association dates to antiquity, when parrots, prized for their ability to mimic speech, were regarded as heralds of emperors. From there, it is a short step: Ave Caesar! becomes Ave Maria!

In Christian tradition, this “Ave” slips into the bird’s beak, turning it into a visual emblem of the Annunciation – the moment when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary with the news of the Immaculate Conception. A parrot, able to mimic human speech, symbolically repeats Gabriel’s greeting Ave Maria! and thus becomes an image of the miracle of conception without sin.

Add to this the wordplay Ave ↔ Eva, and we have a double code: Mary as the antithesis of Eve, the one who undoes the Fall. The parrot, therefore, becomes a symbol of purity, faith, and divine grace.

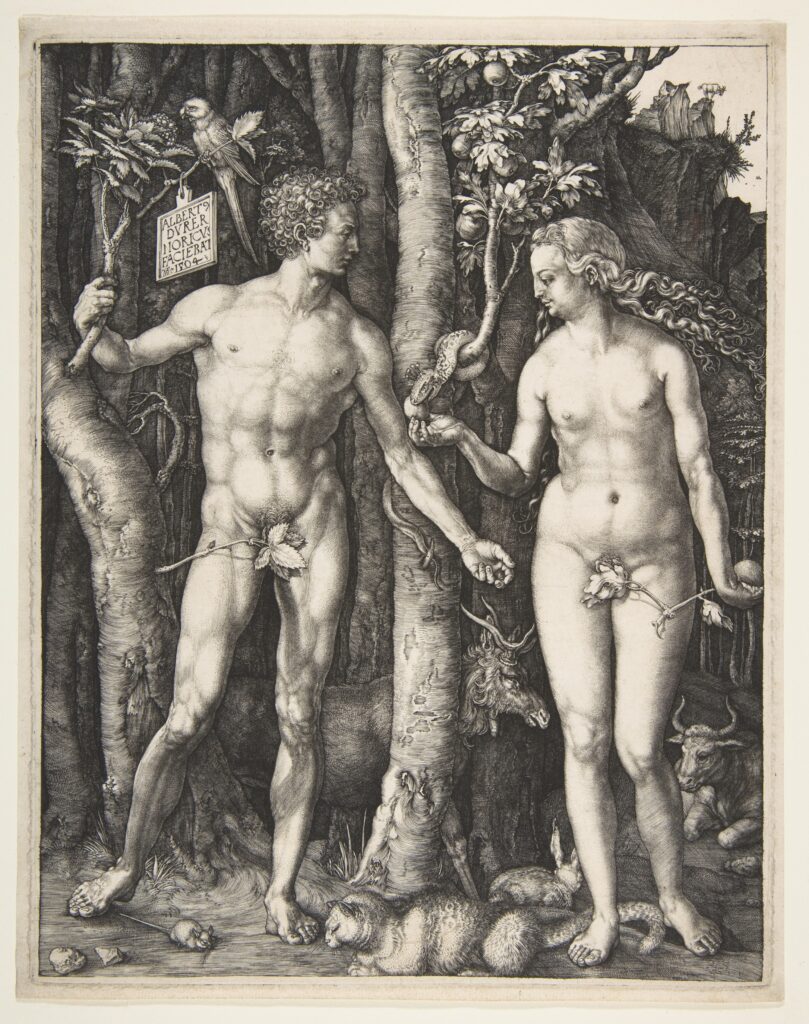

In Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Adam and Eve (1504), the parrot perched above the artist’s signature also plays a significant symbolic role.

In one reading, Dürer’s parrot is a harbinger of the Virgin, a promise of redemption even at the scene of humanity’s first sin. In another, it is a symbol of the wisdom of the Word of God, capable of being repeated and shared. Still others suggest it represents Paradise itself: by Dürer’s time, Europeans imagined the Garden of Eden might lie somewhere in the New World.

Messenger of Love

By the mid-sixteenth century, however, artists were no longer confining parrots to the realm of theology. One striking example of the parrot as a marital symbol is a portrait, possibly of the wife of an Antwerp jeweler, painted by Anthonis Mor around 1564.

The bird rests on the lady’s hand, not as an incidental flourish, but as part of the portrait’s design. Here, the parrot speaks not of theology, but of marriage, fidelity, and marital affection. The parrot had begun its migration from altarpieces to bedchambers.

Symbol of Wealth

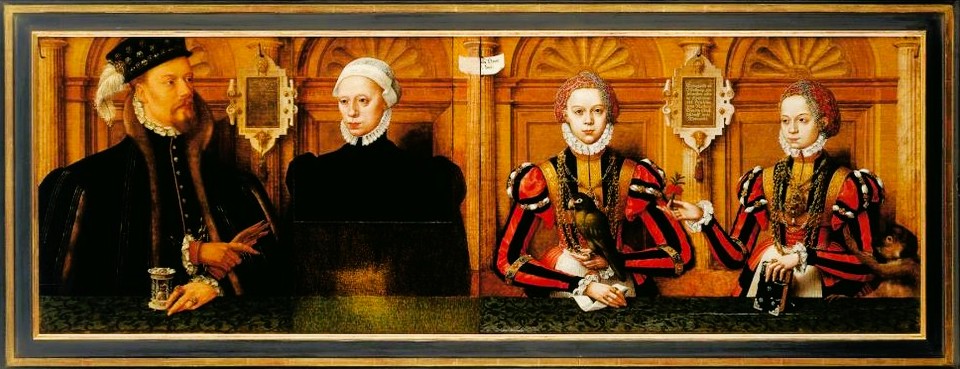

The Family Portrait of Johann II of Rietberg is a textbook example of Hermann tom Ring’s work. The German master of the Northern Renaissance was renowned for compositions dense with symbolic details.

Unlike in religious imagery, where the parrot plays the role of heavenly herald, here it sits in the hands of a girl dressed in the richest fabrics, adorned with pearls and gold. It becomes a true luxury accessory, a marker of wealth, refinement, and social rank. Exotic animals in the Renaissance signaled access to global trade, to discoveries in the New World, and, not least, to the means to afford them.

Seen in this light, the parrot in Hemessen’s painting can be read as a subtle indicator of the couple’s social position. They are not merely idling away time over a game of trictrac; they are doing so in surroundings that speak of comfort, taste, and confidence in their future.

Hero of Genre Scenes

By the seventeenth century, the parrot had shed its halo and settled into genre painting. It appears in the company of courtesans, in intimate domestic scenes with women in dressing gowns, or simply in a cage in the background, a sign of prosperity and a connection to far-off lands.

A faint erotic note emerges: a woman with a parrot could suggest flirtatiousness, caprice, or easy virtue, especially if the bird is not caged.

And as so often in symbolism, just when the system seemed to stabilize, along came Jan Steen to upend it. Ah, Steen! We have already seen him twist the walnut from a sacred emblem into an allusion to earthly pleasures. He does the same with the parrot. In As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young, a boisterous company celebrates the birth of a child: wine flows, music blares, a man teaches a boy to smoke a pipe (the man, incidentally, is Steen himself. And there, in the thick of the revelry, like the cherry on the cake, is a parrot.

What does it symbolize here? Certainly not the Virgin’s innocence. In this loud, almost burlesque context, the bird’s Ave has long since been drowned out. Instead, it mirrors the foolish behavior of adults that children inevitably imitate.

We may have leapt a century ahead in following the parrot’s journey through art, but does that not give us grounds to suspect that in Hemessen’s painting, the bird might mean more than pious love? Perhaps here it is not a heavenly messenger at all, but a signal of luxury, exoticism, and, just maybe, temptation. Especially if it sits beside a glass of wine.

If this parrot truly symbolized the Virgin, as some scholars suggest, why does Hemessen never again use it in his religious works? Among his surviving paintings are multiple Madonna-and-Child images, altarpieces, and moralizing scenes, but not a single parrot keeps Mary company.

Coincidence? An experiment? Or does this small inconsistency invite just a drop of skepticism into the “Marian” reading of the bird in our portrait?

Red Rosary

Among the many symbols in the painting, one element seems, at first glance, impossible to interpret in more than one way: the red rosary, neatly suspended from the woman’s belt. In Catholic tradition, the rosary (from the Latin rosarium – “a crown of roses”) is a tool for prayer and contemplation, a symbol of devotion and daily spiritual discipline.

In the iconography of the late Middle Ages and early modern period, rosaries, especially those made of coral, stand for piety, religious fervor, and moral virtue. A rosary worn at the waist is not just an accessory but a visual declaration: I know what virtue is. Women wore them openly, attached to their belts or held in hand, signaling their focus on spiritual values and reminding both themselves and onlookers that the path to holiness begins with outward discipline.

While exploring Hemessen’s work, we stumbled upon a mysterious portrait of an unidentified young woman, now in the archives of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin and dated to around 1540.

She holds a peach in her hands, her face is solemn, her clothing modest, and at her waist hangs a red rosary that looks almost identical to the one in our painting. Interestingly, at various points in its history, this portrait has been attributed to different artists, including Jan Sanders van Hemessen himself. Today it is catalogued as the work of an anonymous master, but the fact that Hemessen’s authorship was seriously considered for so long cannot help but pique our interest, especially given the symbolic parallel. If this girl’s portrait reads unambiguously as religious in tone, our scene is anything but monastic piety.

In art, a red rosary is deliberately shown on the belts of widows, brides, saints, and others whose virtue needs to be visually underlined. But in Hemessen’s Portrait of a Couple Playing Trictrac shifts the code. Here, the religious emblem is placed in a worldly, ambiguous setting. We see a woman equipped with the outward signs of devotion, playing backgammon with a glass of wine at her side. Is this a mistake? Or a carefully constructed moral riddle? It feels as if Hemessen is intentionally playing with contrast, pulling the symbol into a zone of doubt.

Saints or Sinners?

In Hemessen’s painting, it is not just the symbols themselves, but their placement that becomes part of the game he invites us to play. Look closely: the plate full of fruits sits on the husband’s side. All this abundance is on the surface: a symbol of fertility, marriage, and prosperity, yet also temptation, idleness, and the Fall. In other words, within a single bowl, prudence and seduction sit side by side.

Now shift your gaze to the wife’s side. If we read the symbols in their religious sense, there is the glass of wine, an allusion to the Eucharist; the walnut as a symbol of Christ; the parrot as a companion of the Virgin; and the red rosary hanging from her belt. Here, everything seems to speak of faith, devotion, and purity.

It is as if the objects have been deliberately placed on opposite sides of the trictrac board, like two scales of a moral dilemma the viewer is to weigh. Hemessen presents us with an intellectual riddle, where everything depends on how we choose to interpret the symbols and their arrangement. Hemessen is not the sort of painter to leave symbolism in its “pure” bookish form. He is a master of substitutions, subtexts, and ironic twists.

Take his Weeping Bride, for example: the bride’s head is crowned with a wreath of ripe cherries – an image beloved in the poetry of the time as a metaphor for natural beauty, innocence, and springtime bloom. But Hemessen, almost mischievously, turns this folk symbol into a mockery: the bride’s repulsive face is blotched with tears and snot, a chamber pot in the young man’s hands seems to measure out her future, and the cherry wreath becomes a near-grotesque crown for a figure whose married life will be anything but idyllic.

It is a reminder that Hemessen could reinterpret even the most established, sentimental motif and turn it into an ironic commentary. Which makes us wonder… in our double portrait, could the fruits, the wine glass, the parrot, or the red rosary be far less straightforward than art historians tend to assume?

There is a couple who, like the viewer, have a choice. Do we see here pious newlyweds, united by the emblems of marriage and fertility? Or is this a scene brimming with temptation, flirtation, and broken commandments? The painting can be read both ways.

Jan Sanders van Hemessen gives us no direct answer. Nor does he have to. The artist leaves the moral of this genre scene for us to imagine.

The Final Touch

And one more element that makes us view Hemessen’s symbolism from several angles.

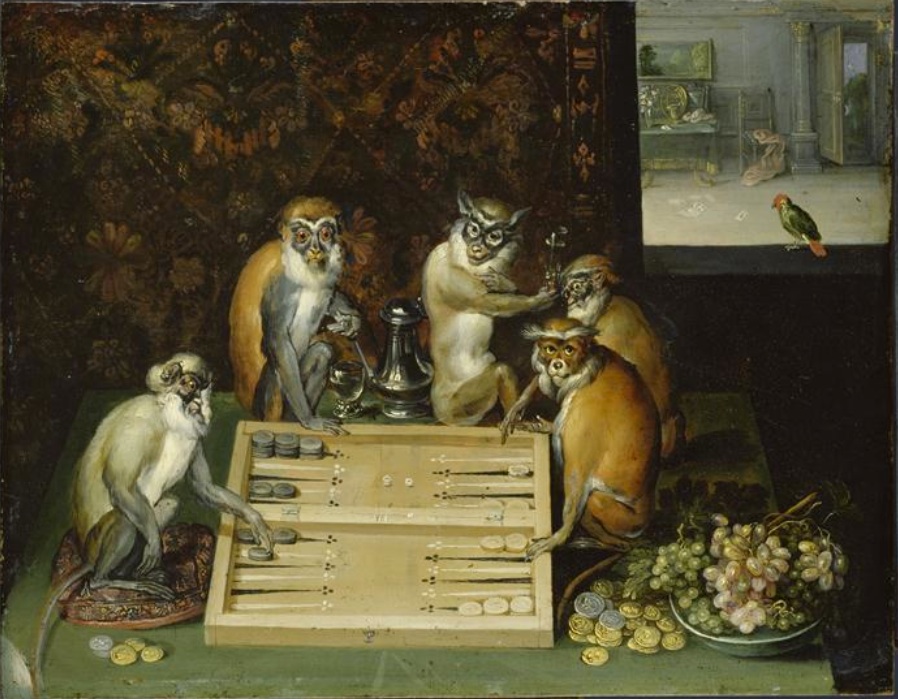

In the sixteenth century, right in Flanders where the artist worked, a curious genre took shape — singerie (from the French singe, “monkey”). Monkeys were depicted in human dress, engaged in human activities, but with deliberate grotesquery and satire. This visual conceit served as a metaphor for human weaknesses, vices, and follies: the monkey imitating man, just as man imitates ideals he does not always live up to.

A particularly intriguing example is Frans Francken’s Monkeys Playing Backgammon. In Hemessen’s world, a pair of lovers is immersed in an intimate, many-layered game; in Francken’s, the players are comical primates, their match a sly parody of human greed and passions.

It is entirely possible Francken had seen Hemessen’s painting, both worked in the same cultural milieu, and that his singerie picked up and reimagined a familiar motif. In his hands, Hemessen’s symbol-laden scene reappears in the next century as satire, almost parody. Francken seems to be saying: Still wondering whether this is virtue or temptation?

Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools is not just an exhibition. It is a once-in-a-lifetime passport into three centuries of Flemish painting. Sumptuous, daring, and brimming with emotion, it gathers under one roof masterpieces that rarely, if ever, leave Europe. And Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s double portrait is here, staring back at you with all its riddles and contradictions.

Opportunities like this do not wait. When the crates close, these works vanish back across the ocean, possibly for decades. So, if you have the chance, do not miss it. The velvet autumn of Toronto is the perfect backdrop for such a journey.

Exhibition calendar

27 Jan 2026

A Guide to Major European Art Exhibitions in 2026

This year is shaping up to be an especially engaging and curious museum season…

Art news

03 Oct 2025

Double Portrait of a Giant and a Dwarf

“Dwarfs” and “giants” were long seen as curiosities of nature. In the Middle Ages…